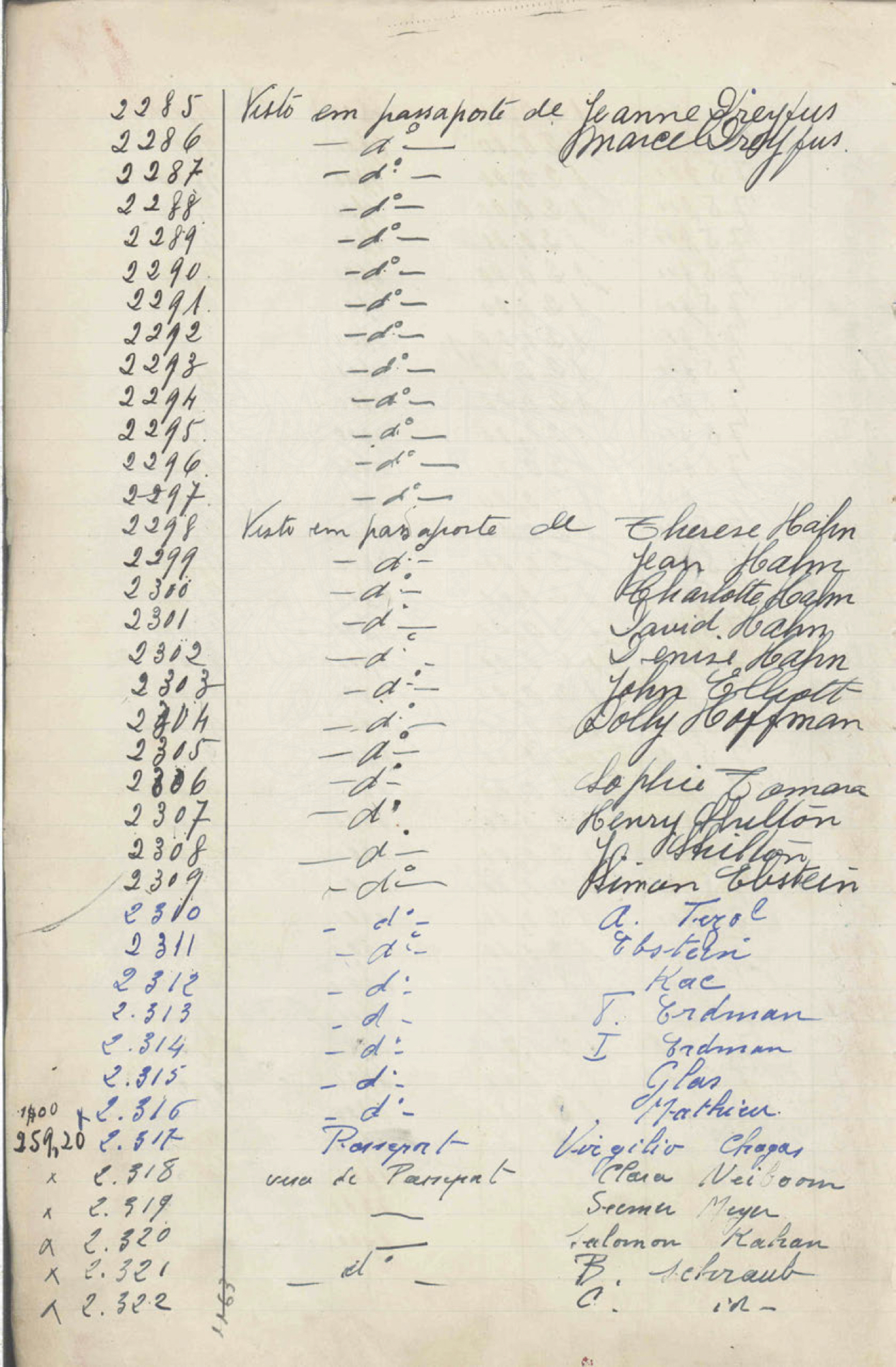

Hahn

Visa Recipients

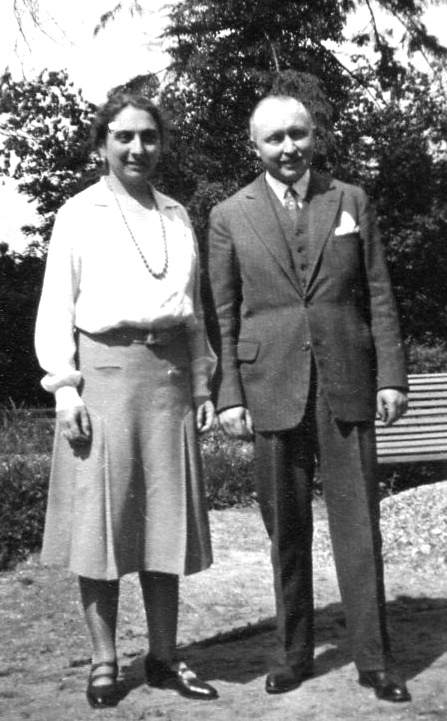

- HAHN, Charlotte née WALK P A

Age 47 | Visa #2300 - HAHN, David Rodolphe P A

Age 51 | Visa #2301 - HAHN, Denise Rachel P A T

Age 18 | Visa #2302 - HAHN, Françoise Micheline

P

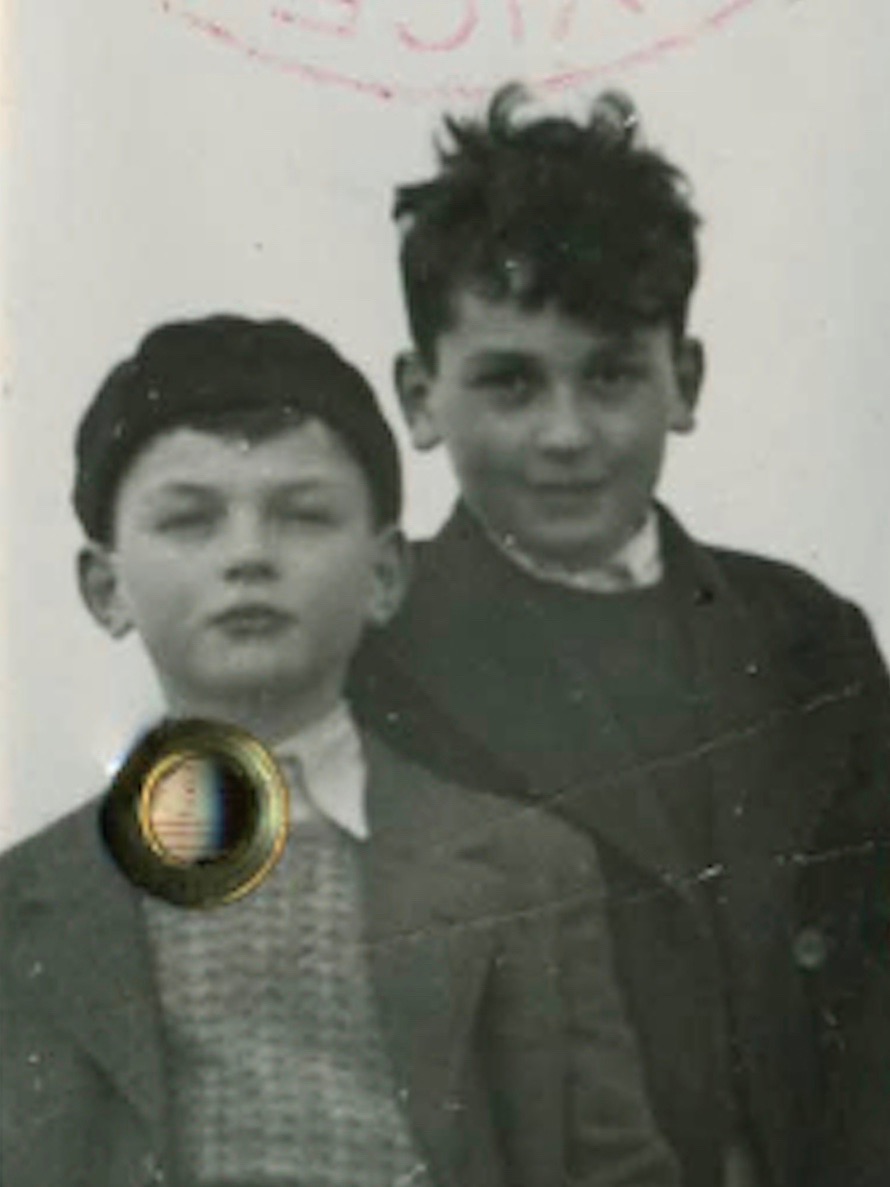

Age 12 - HAHN, Jean Pierre P A

Age 44 | Visa #2299 - HAHN, Pierre Michel V P A

Age 12 - HAHN, Roger P A

Age 8 - HAHN, Thérèse née LÉVY

P A

Age 35 | Visa #2298

About the Family

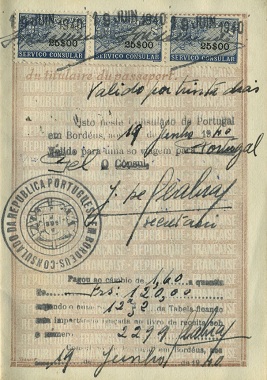

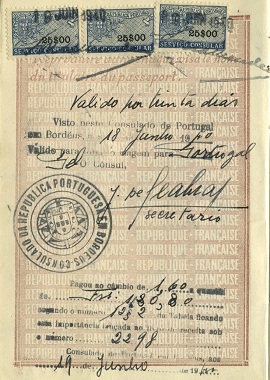

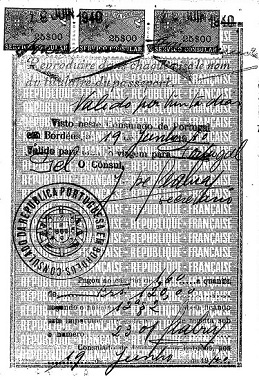

The HAHN family received visas from Aristides de Sousa Mendes in Bordeaux on June 19, 1940.

David and Charlotte HAHN, along with their daughters Denise Rachel and Françoise Micheline, crossed into Portugal and subsequently sailed on the ship Quanza from Lisbon to New York in August 1940.

Jean Pierre and Thérèse HAHN, along with their sons Pierre Michel and Roger, were turned back at the French/Spanish border and remained in occupied France for another year. Eventually they sailed on the Ciudad de Sevilla from Barcelona to New York in August 1941.

- Video

- Photos

- Artifacts

- Testimonial

Testimonial of Denise HAHN

As refugees, we were extremely moved by the way the Portuguese, in particular the poor ones, received us, in spite of the fact that Portugal was governed by a hard fascist hand. They received us as the dearest friends would have done. This tells all...

Getting visas was regarded as a miracle. Our guardian angel was Dr. Aristides de Sousa Mendes, consul general of Portugal in Bordeaux... He decided to stamp our passports, as well as hundreds, and soon thousands, of refugees' passports.

The Spaniards gave us a three-day transit, which enabled us to reach the Portuguese border. Within twenty-four hours we were booked on the direct express to Lisbon on a luxurious, incredibly long train. In the middle of the night, the train stopped. We had reached the Spanish-Portuguese border. Everyone was ordered off the train. As the light lit the small station, we recognized some well-known figures: scientists, writers, philosophers, etc. to whom "liberal France" had guaranteed her "protection"! But since France had signed an agreement of collaboration with the Germans, all her promises were nil. Obviously, the French who heeded de Gaulle's call to continue the fight (in the colonies, in England or in France in the underground) were still too few...

We met young mothers, sometimes with a grandma, with tots from our Paris neighborhood! All hoped to continue the trip as planned. Rumors flourished. Would we be sent back to collaborationist France? This was the greatest fear, our big nightmare. All these rumors came to nil when the big train disappeared during the second night. My father, who spoke several languages, and always kept a calm and polite attitude, managed to communicate with the head of the station: "a man of authority should be arriving soon." The employees were all very courteous.

What about the local villagers? They immediately invited elderly people and mothers with young children in their homes.

On the second day they gave us all in turn some time to lie down and rest on their beds, all made of wood and mattresses of wood shavings. They brought out food for the children: bread, eggs, whatever they had without ever accepting a penny. By their gestures, some talking and singing, they managed to communicate with us...

We understood that soon there would be a decision concerning our fate in Portugal. On the fourth day the "decider" appeared. He was the Lisbon police chief. He immediately said, in a calm and polite tone, that we would not be sent back to France... The authorities would assign towns of residence to each family.

At first the refugees were shocked, and even more so when they were told that they would have to hand over their passports to the authorities. What, they said, would happen if they needed to apply for admission in a foreign consulate? All was smoothed over in a calm and polite tone. At no point did the refugees feel they were treated like unwelcome intruders. Everything was taken into account. We could retrieve our passports to enable us to attend to our business as often as necessary. We were impressed by the logic of these decisions and the courtesy that went with it.

Our family was fortunate in being sent to Oporto. Here begins the story of our life in Portugal (a year and a half). We stayed in a modest hotel whose director made it a point to sit alone (when he could) with my father in his office and tell him (in English) a little bit of the feelings of most of the neighbors. Thus he hinted quietly what many Portuguese people thought of the political regime. Extreme prudence was necessary.

In the neighborhood we got the same message from the local merchants in a different form: a warm greeting to the "Francese," insisting on giving us extra free fruit along with a gesture of friendship. The message was clear: you are special, you refugees. God bless you. In this beautiful old town we could "breathe" the modesty, the honesty of a people so generous and so genteel. When I learnt a few words in Portuguese, it was one more link of friendship.

Here begins our life outside Oporto, let us say in the outskirsts. It was very hot, so we sometimes sat in the park: my older sister (a grown-up lady!), myself (seventeen years old) and my little sister. No man to watch over us. We quickly understood that this was unacceptable behavior for proper folks. So we sometimes took the tramway to the shore. The sea was not far off. Passing by the harbor, we saw barefooted women carrying heavy sacks of coal on their heads, walking on sharp stones, sometimes mixed with broken glass. When we could approach them, if no one was looking, we would slip a few coins in their hands. The glance we got was the most precious gift I ever received. It contained the truest expression of gratitude, love, generosity and dignity come from the most oppressed among the poor.

The same kind of qualities were to be found among some of the U.S.A. consular personnel. Among the vice consuls one spared no effort to hasten the procedure. He was a typical "yankee," generous and friendly, eager to implement the process "without dragging his feet." He felt that anything which would shorten the pain of the persecuted would strengthen the words inscribed on the Statue of Liberty.