Asinsky/Neulinger/Serebriany/Tenenbaum

Visa Recipients

- ASINSKY, Esther née CHARMATZ P

Age 59 - NEULINGER, Dora née ASINSKY P

Age 39 - NEULINGER, Marie Isabelle P

Age 9 - NEULINGER, Philippe P

Age 45 - SEREBRIANY, Golda née ASINSKY P

Age 35 - SEREBRIANY, Hirsch

Age 35 - SEREBRIANY, Léon

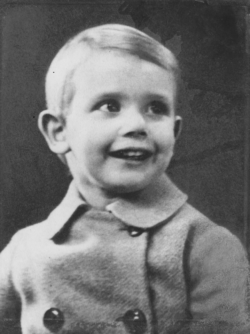

V P T

Age 4 - SEREBRIANY, Raymonde Estelle P

Age 7 - SEREBRIANY, Sigismond P

Age 18 - TENENBAUM, Icek P A

Age 40 - TENENBAUM, Mase A

Age 2 - TENENBAUM, Monique A

Age 3 - TENENBAUM, Rosa née ASINSKY P A

Age 31

About the Family

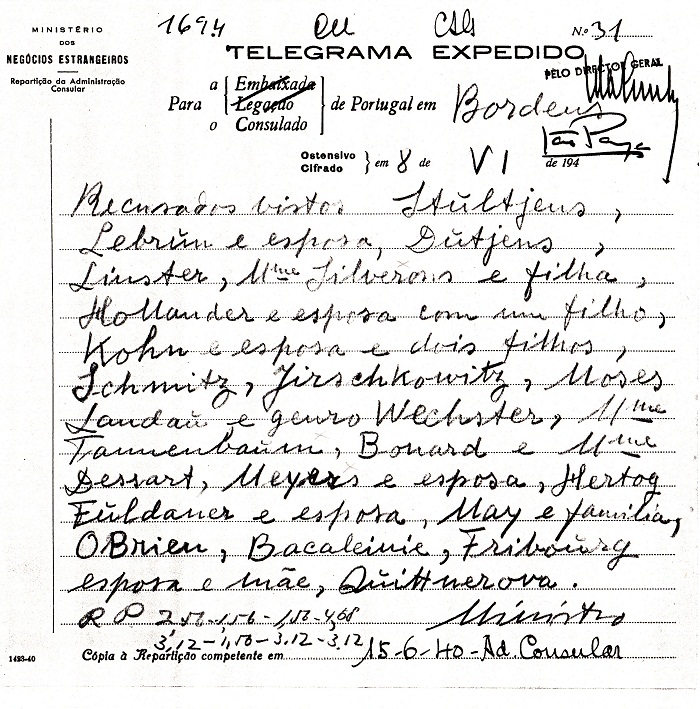

These families were issued Portuguese transit visas authorized by Aristides de Sousa Mendes in Bayonne, France, in June 1940.

They crossed into Portugal, where they resided in Figueira da Foz, lodging with a family named Ferreira. Icek TENENBAUM sailed on the vessel Quanza from Lisbon to New York in August 1940. His wife Rosa TENENBAUM and their children Monique and Mase followed on the Nea Hellas in October 1940. Raymonde SEREBRIANY, age 7, fell gravely ill in Portugal and died due to the unavailability of the new wonder drug, penicillin. After burying their daughter in Portugal, Hirsch and Golda SEREBRIANY, their son Léon, and Golda's mother Esther ASINSKY, sailed to New York on the Lourenço Marques in February 1941. Sigismund SEREBRIANY followed on the Serpa Pinto in March 1941. The NEULINGER family sailed from Lisbon to Philadelphia on the Serpa Pinto in June 1943. Esther ASINSKY's daughter, Berthe BLIOKAS, obtained a Portuguese visa in Toulouse.

- Video

- Photos

- Artifact

- Testimonial

Testimonial of Lee STERLING né Léon SEREBRIANY

On May 10, 1940, I was 19 days shy of my 4th birthday. We lived at 40, Blvd. Dixmude in Brussels, in an elegant apartment with large windows in the front room that my father used for his diamond wholesale business. The windows were covered by heavy, soft, velvety, maroon drapes. In the morning, I heard loud noises I had never heard before, and rushed to the front windows and pulled aside the drapes. Suddenly, my father was at my side, taking me by the hand and pulling me away from the window. He didn't say why, and I didn't know that the sounds I heard were bombs being rained down upon us by the German invaders.

Family conferences were held over the weekend, and, finally, on Sunday, the 12th, my mother insisted that we leave Brussels. Because of the immense crush of cars and people on the roads we traveled at a snail's pace. My parents had been told that the French were allowing Belgians into the country, and fortunately, my mother insisted that my father drive us to the border. By the time we got there, we had to wait overnight. In the morning, my sister Raymonde fell in a ditch and suffered a serious cut on her leg. A doctor we had met while waiting in the line of cars disinfected and bandaged the wound. But, she needed a tetanus shot, and for that we had to drive to Dunkirk. The roads were jammed, and petrol was hard to get. My father realized that we could not get back to Brussels!

We met up with family friends, and together we all drove to Cabourg. On the way, one of the four cars in the group turned over into a ditch. The driver and his sister were seriously injured, and her 4-year-old son was rushed to the emergency room of the hospital in Caen, where he died. The group stayed in Caen for several days to arrange the funeral, and to have some time for everyone to come to grips with the tragedy, and for the driver and his sister to recover.

The group decided to head south, and we settled in a small town, Taussat, 30 miles west and a bit south of Bordeaux. But, the Germans kept advancing, and my parents decided to drive to the Spanish border, and we headed for Bayonne. Thousands of people were there ahead of us. My mother, and her sister, Rose, decided to find out how to get across the border. The story I've been told is that they discovered an office where visas were being issued, and, somehow, got us visas to get to Portugal. We arrived in Figueira da Foz sometime in late June. It's a beach town, and apparently my sister and I had a good time going to the beach, playing in the park, and going to the movies. But, my seven year old sister, who doted on me, and was the joy of my parents, died in Figueira da Foz of dysentery because penicillin was not yet available to cure that horrible disease.

Overcome with sadness, and with hope for the future, we left Lisbon on January 27, 1941, on the Loureno Marques. We arrived in New York on February 8, 1941, several months prior to my fifth birthday. I have few recollections of the adventure I've described. The information comes from a letter that my father wrote to one of his brothers in August of 1940, which was discovered by his daughter just a couple of years ago.

That was all I knew about how we got to Portugal and how we, ultimately, got to America, until August of 2012, when I did an idle Google search of various family names. The last name I decided to try was my maternal grandmother's married name. That turned up a page with startling information. It showed that our family was issued visas to freedom by the Portuguese consul, Aristides de Sousa Mendes, allowing us to go through Spain and into Portugal, against the orders of the Portuguese government.

Additional research led me to a video showing how some other Sousa Mendes visa recipients got to Figueira da Foz, and that solved the mystery for me of how we ended up there before getting on the ship that brought us to America.