Gingold

Visa Recipients

- GINGOLD, Hedwig née GRABSCHEID P T

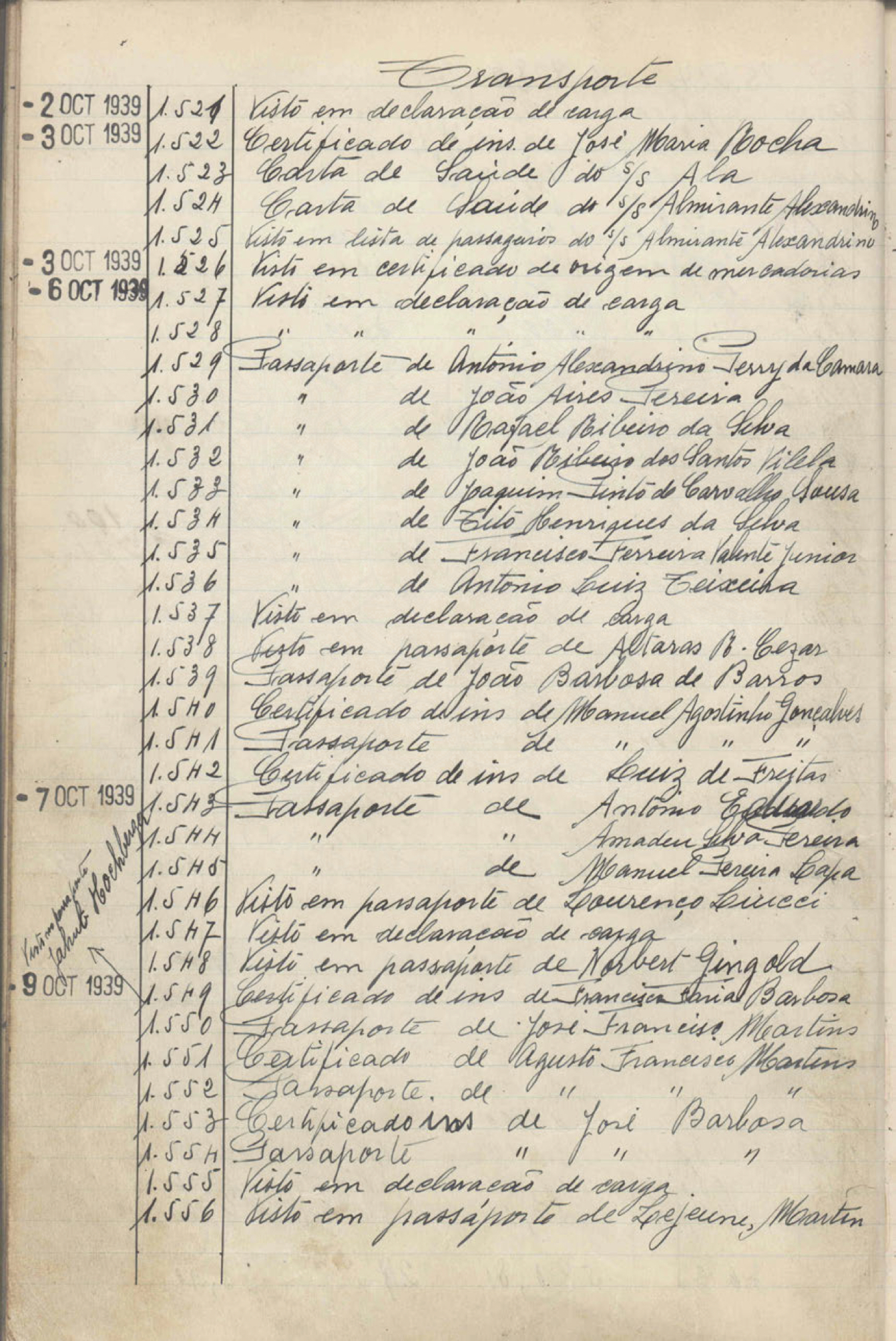

Age 39 - GINGOLD, Norbert P A

Age 37 | Visa #1548

About the Family

The GINGOLD couple from Vienna received visas from Aristides de Sousa Mendes in June 1940. In addition, the numbered visa was issued months earlier, on October 7, 1939.

Norbert GINGOLD was a composer of children's operas who conducted the premiere of Kurt Weill's The Threepenny Opera.

In October of 1939 he was in an internment camp in France as an enemy alien, and Aristides de Sousa Mendes personally went to the camp to try to obtain his release. This was unsuccessful, but he was released at a later date. The GINGOLD couple reached the French/Spanish border at Hendaye/Irun too late and were unable to cross, as by then all de Sousa Mendes visas had been declared invalid by the Portuguese government. They spent the war years in hiding in Marseille.

They later emigrated to the United States where Norbert GINGOLD founded the San Francisco Children's Opera company.

- Photos

- Artifact

- Testimonial

Testimonial of Heddy GINGOLD

Excerpts from The Lucky Village

The railroad station was full of people. Most of the men were ready to join their regiment.

"Where will we go?"

"Let's go to Bordeaux," he said. "It's a harbor and we might get a visa there and a ship." ...

I don't remember much of the trip that we made on the crowded train. The only thing that I know is the shock I experienced when I saw a gas mask for the first time. It looked gloomier to me because a priest was carrying it around his neck. In his black outfit and with that mask hanging on a chain around his neck, he seemed to be the impersonation of war and disaster.

I looked through the window. There it was again. The sign on the station: LIBOURNE. I had no premonition that in the future, I would often come to this town.

THE VISA FOR PORTUGAL

I knocked at the door of the Consul's office. Hundreds of thoughts whirled around in my head. Will he be as short tempered and unfriendly as most of the other consuls had been? It is true that the others were not consuls, just employees. I had never reached a consul personally. And so far, I had always received the same answer: no visa on an Austrian passport. Will I get this answer again? Maybe not. Maybe he has a heart for the misfortune of innocent people. After all, he was willing to receive me. Or maybe he makes a business out of our misfortune and will charge me an amount I could never pay. What will I say then? I felt a very heavy responsibility on my shoulders. Wasn't Robert's destiny in my hands? Weeks ago, I had found out that his lodgings were simply a dark, dirty wine cellar with moisture on the walls, humid and cold. Robert had a serious illness, a throat infection, only two years ago. How will he stand such treatment much longer? I heard a voice saying "Entrez!" Oh my God, help me! Let me obtain the visa, I prayed.

When I left the office half an ohour later, I was not walking, I was flying on a pink cloud. I had visas for a stay in Portugal! And they were unlimited, also. We are saved! Robert will not have to remain in the camp and we will be able to leave France instead of waiting for a bombing that may happen at any moment.

That evening as I lay in bed, looking as usual at my fluorescent flower, it suddenly became a round full moon. I was in Portugal. Couples were walking in winding streets, lovers were playing their mandolins under the balconies of their sweethearts. There was laughing and singing in the air, and there was freedom and happiness.

The first thing that I did in the morning was to go to the police station and to ask for a permit to visit the camp of Libourne. For the last two months, there were no visits permitted anymore without an authorization.

"You already had one this week," the police officer told me. "We are not entitled to grant you a permit more often. You people are lucky anyway. My wife, for instance, had to stay in Paris and I am employed here. I haven't seen her for three months."

"I am sorry for you," I answered, "but you have a job here, haven't you? My husband is a prisoner, and it isn't his fault."

"Que voulez-vous? C'est la guerre."

But he gave me the permit when he heard about the visa.

The twenty miles that I had to ride in the bus passed faster than ever before. I was making plans. Robert would come home with me this very evening, and tomorrow we would leave Bordeaux for Portugal. It was very exciting! How strange that without this war, I probably never would have seen Portugal.

I hurried from the bus stop to the camp.

"Robert!" I shouted as soon as saw him approach. "We've got the visa!"

Robert was excited as I. "Quick, give me the passport!" he said. "I will show it to the Captain!" Then he ran away with it.

I mentally said goodbye to the river enveloped in its clouds of mist, to the huge vineyards now emptied of their precious load of grapes, to the cabins of the camp wardens and to the wardens themselves. In my happy mood, I saw their real faces for the first time. Most the them were unhappy. They, too, wanted to return to their civil life, to their homes, to their jobs. Wasn't it awful to hang around, watching a bunch of other unhappy men, innocent and helpless, prisoners without a crime? ...

Robert came back very disappointed. The Captain was out of town, and so, once more, I had to leave alone. We will have to wait until tomorrow. Never before had I realized how long it can be until tomorrow.

The next morning I began to wait for Robert's homecoming....

Dora walked in my room four steps forward, four steps backward. Suddenly she stopped as if she were touched by an idea.

"Say, what kind of a man is this consul of Portugal?"

"He's fat and round, middle-aged, with dark hair and eyes. I guess that he looks like most of the people from there."

Dora stamped impatiently on the floor with her foot. "I don't care how he looks. Tell me, was he friendly when he gave you the visa?"

"He was the only consul to grant me a visa. That's the most friendly action he could perform. He was really kind. He didn't ask me any questions as soon as he heard that my husband was in the camp. And besides, he charged the normal price of the visa, not a cent more."

"That's perfect. You go right away to him and tell him that they refused to release your husband."

Then she told me that she had heard from other refugees that the consul had helped many Jews leave France by according visas to them. But those people had not been in a camp. I don't know why we did not try to obtain a visa before Robert entered the camp. We must have become discouraged by so many refusals.

Once more, I went to the Consul, and he listened sympathetically to my story.

"Yes, it is a 'drôle de guerre' we have now, and innocent people have to suffer."

"What do you advise me to do?"

He smiled. "I will try to help you, Madame. If you want me to talk to the Captain of the camp..."

"Yes, yes, of course," I exclaimed. "Oh, I am so glad! I am sure your intervention will free my husband."

"I'm not so sure of that but I will do my best."

I invited the Consul to come with me in Mr. Muss' car, and next morning we were on the way to Libourne.

I didn't ask for a permit because I thought the presence of a foreign Consul would be sufficient to enter the camp. But we didn't have to visit the camp at all since we were told that all the prisoners were working in a vineyard. And since I wanted of course to introduce my husband to the Consul, we drove over to the farm where the vineyard was located.

It was October [1939] and most of the fruit was gathered, but there were still a great number of unharvested vines where our prisoners worked.... I was amazed how pale and tired the men were. Robert couldn't stand straight. His back was stiff from bending over. He looked ill. I was very afraid that he might really get sick and I was saddened about all the other men who looked so pitiful.... It isn't a tragedy to pick grapes, but no one should be forced to do it. And it was a waste of creative forces which could have been used in a better way.

At the end of our visit, the Consul went back to the camp and was received by the Captain. When he left I knew that all our hope had been in vain. There was nothing to do. Only an overseas visa could free Robert.

Two months passed by.... It was the middle of December [1939] when I got the permit to go to Paris. Robert had suggested a long time ago to give up our big apartment and store away all its contents....

By the next morning, I was in Bordeaux again. Some weeks passed without incident, except some bad news from the front. The danger of France being invaded by the Germans came closer and closer, and our anxiety rose higher and higher. I went to Libourne as before. Both Robert and I became more and more pessimistic. As time continued to pass on, we hardly saw any possibility of getting out of this predicament....

The first of April [1940] arrived with all its splendor in this part of France. I came home, exhausted and sad. I had given up the hope of seeing Robert before long.... How startled I was when I noticed a telegram in the early morning hours. It had been tossed on the chair. The evening before, I had been absent minded totally preoccupied with my own problems. I just didn't see it. Now, I was very eager to learn the news that it brought me. I quickly tore it open. And then I had to sit down because my knees were shaking and I almost cried...

The telegram came from Robert and it was very short. It just said: COMING HOME -- ROBERT.

My goodness, how much can you say in just two words! He was coming back! There it was, the fairy tale I had dreamed of and waited for so long! I couldn't figure out how it was possible that he was freed. But my heart was in jubilation. He was coming, and he wouldn't have to wait to be captured by Hitler's hangmen, and we will be able to escape. How? Well, somehow.... Suddenly, I heard somebody enter the room. I turned around... There he was, Robert, wearing his own suit instead of the old uniform. He was FREE!

After calming down somewhat, we sat on the trunk-coffee table and there have never been two happier people than us....

It was five o'clock in the afternoon when we approached Hendaye, the village which is the last in France, at the Spanish frontier.

"Stop right here," said Robert to the driver. And then he told me to wait for a moment in the car. "I see the Spanish consulate where I must get the transit visa. That is a formality which will just take a few minutes. But after all, Hitler is not here yet. There's no need to hurry."

He stepped out of the car, but after a second look at the little house, he turned around.

"It's too late," he said disappointedly. "See, the janitor is closing the gate. It's exactly five o'clock. We will have to stay in this village until tomorrow."

I sighed. "I wish we hadn't taken that cup of coffee in Oloron. That's why we are late."

"Well, now it's done. We'll just arrive in Portugal a day later."

"But where will we stay overnight?"

"We'll have to look for someplace."

That seemed simple at first. But we soon found out that it was out of the question, because with every half hour that passed, thousands and thousands of refugees coming from the North flooded over this little town until it was drowned in the stream of despairing humanity. All the inns were entirely full. There wasn't even a chair free in any cafe, no private apartment had a free bed, no bench on the street had a space to sit on.

As we left the edge of the village and entered the center section, we discovered that this state of panic must have lasted for days already, for whole families were camping on the tracks close to the railroad station which was located in the middle of the main square.

"Look, isn't that our friend, the consul of Portugal?" I exclaimed.

"For sure it is he!"

The consul stood there, surrounded by a group of refugees, giving out visas to anyone who asked for them.

"He is a good man, he wants to save all these people."

"Yes, he is a nice person. We'll pay him a visit when we are in his country." ...

The next morning, we woke up very early and dressed quickly and hurried to the consulate. It was closed.

"It's after nine o'clock. I can't understand," said Robert.

"Neither can I."

But soon we understood. The bells of the old church in town started to ring the Mass. It was Sunday [June 23, 1940]! We had forgotten time in the emotion of the events that we had lived through....

There was the ocean beaming in the sunshine. And right there at the horizon was Irun, the Spanish frontier town. There it was lying, and since the air was clear, we could see it close enough to distinguish the old tower....

"Where will we turn our tired steps now?" I asked, trying to show some good humor despite all of the adversity.

"Let's go to the bridge."

"Yes, come on," I exclaimed, so excited, because we had been told that the bridge which connected Hendaye with Irun was the frontier, and I wanted to see right away the place where we would enter Spain, tomorrow!

"Isn't that a crowd!" I marveled when we stood before the bridge where French and Spanish soldiers controlled the crossing of the people. The Spanish guard looked as if they had come right out of an operetta with their colorful uniforms and their black lacquered helmets. But the refugees looked like characters out of a tragedy. And that's what we all were.

"What is going on in the little house over there?" I asked Robert. I saw so many people going in and out, their identification papers in hand.

"I'll inquire," said Robert and went into the cabin. After awhile, he came back, radiant. "I've got the visa!"

"The Spanish transit visa?"

"No, the exit from France."

"Isn't that the same visa that we couldn't get during all these past months?"

"Exactly. And now we have it."

"Wonderful!"

"The [Spanish] transit visa is the only one missing, and we can leave behind the whole nightmare of war and start a new life. It's a shame I didn't get the Spanish visa in Bordeaux at the consulate there. We could have left today."

"Why didn't you?"

"There were too many people waiting in line. I guess I just waited for you to leave the camp and wasn't interested in anything else."

"Well, it's a delay of only 24 hours. It doesn't matter very much, does it?"

"I don't think so."

"But the Germans are coming closer. When I was waiting for you, I heard people say that their troops have passed Bordeaux. They are on their way here."

"I don't believe it is true. But if it were so, they can't approach so quickly. They are not riding comfortably in a pullman car."

"Let's hope so. But anyway, I can hardly wait for tomorrow." ...

We did not sleep that night and woke up in the morning [June 24, 1940] as early as five o'clock.

"Let's go right away to the consulate. There will be a crowd, and this time we must not be too late."

What was that odd little noise on our windows? We looked out. It was rain pouring down.

"Couldn't we go later?" I asked meekly. "I am sure that they won't open before nine. We will have to stay outside in the rain for hours."

"Never mind." ...

It was not easy to reach the bridge. The crowd of refugees had swollen like a wild stream. There were many private cars with mattresses on top, as a protection against bombs. Other people came on bicycles. We also saw a sick man in a wheelchair. And then, there were the pedestrians, walking like us. There were thousands of them....

We almost could not see the bridge because of the crowd. Many people stood in front of a poster reading it attentively.

"Let's see what it is!"

We approached close enough to read the announcement. There it said, deadly clear, impossible to be misinterpreted:

ALL VISAS FOR PORTUGAL DELIVERED IN BORDEAUX ARE VOID.

"We got our visas in Bordeaux," we both exclaimed at the same time.

"But why? But why?" I said, and real despair took hold of me.

"Don't you remember the consul standing yesterday here in the street, giving out visas to everyone?"

"Yes, I do."

"He probably gave out too many. They noticed it in his country and these are the results."

"And he will lose his job, this poor man. He has fourteen children to raise. He wanted to save people, that is why he did it."

"Yes, he was charitable to everyone. But we got our visa properly, a month ago. Why should it be void?"

"That is still to be found out. Let's hurry to the [Spanish] consulate. Maybe this order doesn't concern us, since our visa is much older." ...

We were completely soaked when we reached the consulate.... At nine, the door was opened and we entered, but of course, we had to wait for one more hour until our turn came. But then, it was short. In fact, it was too short, because we didn't even have a chance to show our passports. They immediately refused us a transit visa since our visa to Portugal was issued in Bordeaux.

NEXT, PLEASE!

There we were in the street again, shivering in our wet clothes in the sunshine which at last had overcome the enemy rain.... We were starving, but there wasn't any food to be had. It was the twenty-fifth of June and declared a national mourning day because of the defeat.