Kaufmann/Koch

Visa Recipients

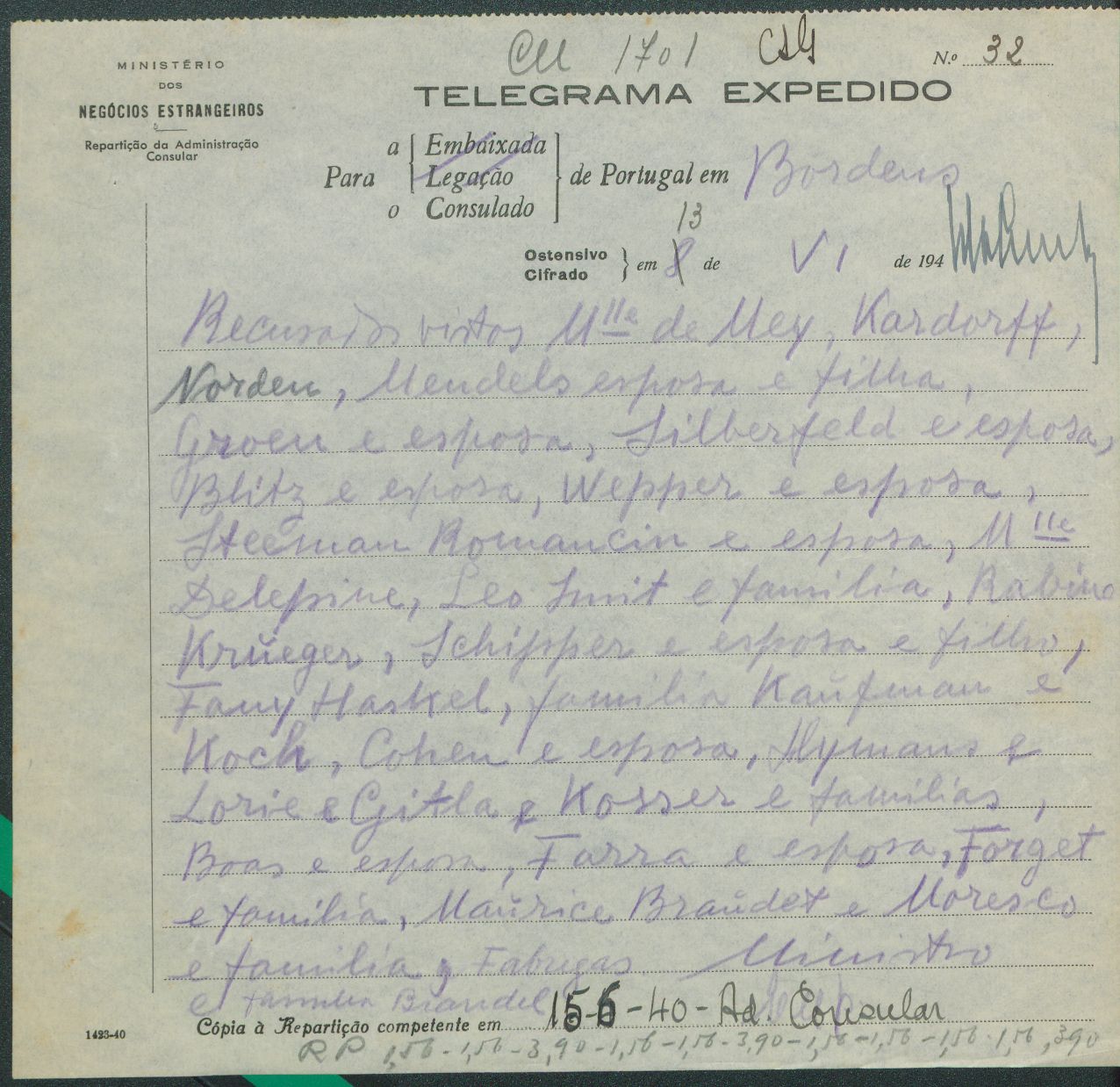

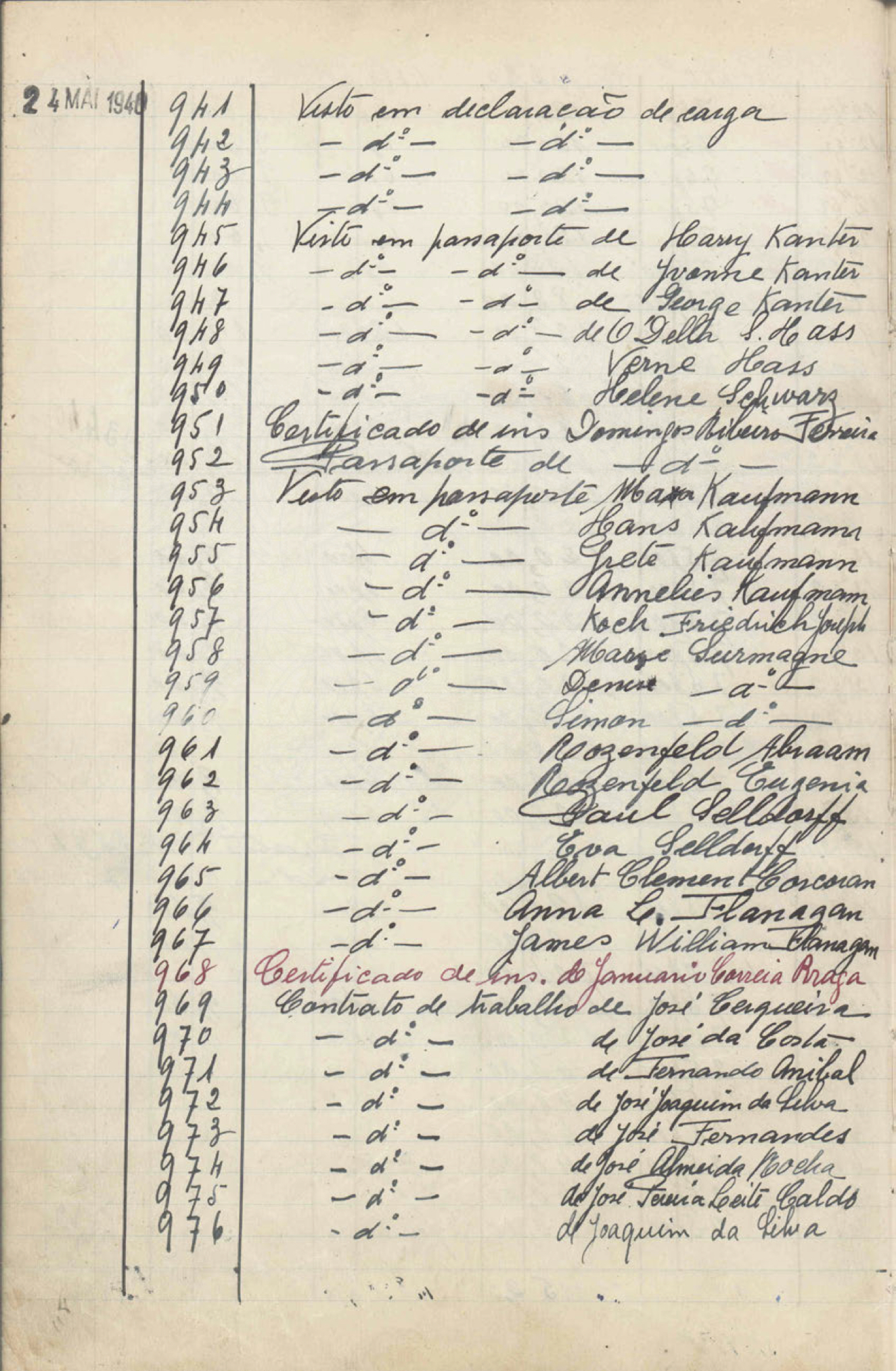

- KAUFMANN, Annelies P A T

Age 17 | Visa #956 - KAUFMANN, Grete Jeanette Marie née ROTHSCHILD P A

Age 47 | Visa #955 - KAUFMANN, Hans Herbert P A

Age 14 | Visa #954 - KAUFMANN, Max Jean P A

Age 47 | Visa #953 - KOCH, Friedrich Joseph A

Age 51 | Visa #957

About the Family

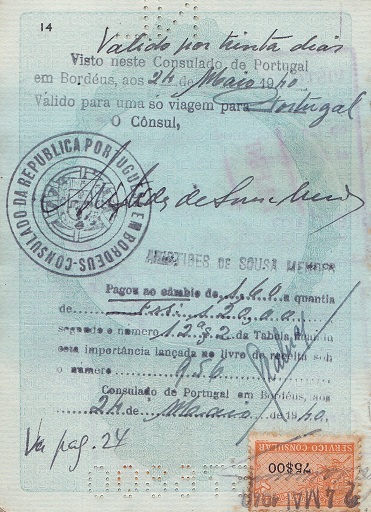

The KAUFMANN family and Friedrich KOCH received visas from Aristides de Sousa Mendes in Bordeaux on May 24, 1940. These visas had been explicitly denied by Salazar, the Portuguese head of state.

They crossed into Portugal, where they resided in Caldas da Rainha. Max KAUFMANN and Friedrich KOCH flew from Lisbon to New York on the Dixie Clipper in October 1940.

Grete KAUFMANN and her children Annelies and Hans sailed on the ship Siboney from Lisbon to New York in December 1940.

- Photos

- Artifacts

- Testimonial

Escape From War

Testimonial written by Col. James B. Barrett, husband of Annelies Kaufmann

In early May, the Kaufmans, in the family Graham-Paige four-door touring sedan, accompanied by Uncle Koch (OK) in his Packard, drove south almost to the Belgian border, to a resort hotel named Anneville, not far from Breda, for their vacation. (A 2007 computer search reveals a Koetshuis Anneville in Ulvenhout, near Breda.) The family played tennis, rode horseback together, as was their holiday custom, and they relaxed until the fateful evening of May 9, when the radio brought reports of German troop activity at river crossings across the Maas and Rhine, and of bombings of nearby Dutch towns.

Checking out hurriedly the next morning, their route towards home soon took them past a military airfield at Gilze-Rijen, home to Dutch fighter squadrons. As they approached the airfield, to their dismay they were looking at a sky filled with descending German parachutists. World War II had suddenly come to Holland on May 10, 1940 and life for Anne, age 16, and her family, as for so many others, was never to be the same.

Seeing their way home barred by invading Germans, the Kaufmans and OK had turned their cars around and sped back to the hotel, remaining overnight, while news reports made clear that immediate departure south was their only choice. Obtaining blankets and temporary provisions from the hotel, the next morning the five of them, in their two cars, headed for the Belgian border. Crossing it, they reached Ghent, where they spent the night in the cars, bundled in the hotel blankets.

The second day they crossed into France and reached Rouen. The Germans, having protected their northern flank and ensured access to vital Swedish coal supplies by invading Norway and Denmark in April, next invaded Belgium and Holland in May, providing maneuver room for an envelopment to avoid the Maginot Line defending northern France. They were now in the process of unleashing their armor and mobile infantry divisions in blitzkrieg tactics against France. They began the invasion of France on May 14, 1940 and reached the English Channel on May 21. An unwise German decision was made to depend solely on the Luftwaffe and infantry to destroy the trapped Alliied forces, while their armored divisions refueled and made repairs. This had permitted the dramatic escape of much of the British and French armies, beginning May 26, across the beaches of Dunkirk.

When the Germans invaded France on May 14th, Anne’s family and OK had reached Bordeaux. The fortunes of war had favored them so far, thanks to their choice of holiday location close to the Belgian border. Similarly, by extraordinary good fortune, Max’s brother Fritz had been visiting London when the Germans invaded Holland. His pre-teenage son, Frank, was with him, an only child who had lost his mother in childhood. In Bordeaux, Max contacted a vineyard owner and wine merchant, one of his suppliers, who then provided shelter to the group in his own home while they made final plans to cross into Spain.

Thanks to their business relationships with Monsieur Eschenauer, their host, he was able to provide access to funds. He also telephoned the French border authorities and learned that no automobiles could leave the country without a special permit guaranteeing their return. Since delay, with the possibility of not obtaining such approval in the end, could not be risked, he arranged with the authorities to accept temporary custody of the two cars at the border, and hold them pending their owners’ return. Herb recollects that they remained in Bordeaux the better part of a week. However, the military situation kept deteriorating, so the group next drove to St. Jean de Luz, in the southwestern corner of France, then on to the border, close by at Hendaye, where they delivered the cars into protective custody without disclosing their intent not to return.

Crossing into Spain on foot, they boarded a train west to San Sebastian on the Spanish coast, stopping overnight at a hotel. There is humor in even the direst situations and both Anne and Herb separately recounted an incident at dinner that night, a welcome feast. The weather had been hot, air conditioning did not exist, and the children watched, fascinated, as a bead of sweat slowly made its way down the waiter’s nose as he ladled out the soup, finally dropping into one of the bowls. Herb remarks, “All I know is that it wasn’t mine.”

Spain was under the rule of Franco, recovering from years of brutal civil war during which he had been supported by Hitler. Max and OK decided it was imperative to proceed by train to Bilbao, further west, then continue south to the safety of Portugal, a neutral country, starting out the next day to where better options awaited them. That grim trip south from Holland was burned into all their memories, but one recollection in particular remained with Anne, when, tired and hungry after crossing into Spain, at one of the train stops they had purchased sandwiches from a station vendor and, in addition to their other problems, Anne became desperately ill from tainted meat.

Years afterward, Greta had marked their route to safety in a family atlas, tracing it in ink, adding the title “Our Flight (Escape) From Europe.” It showed a line from Holland south thru Antwerp – Ghent (overnight) – Lille – Amiens – Rouen (overnight) – Le Mans, then southeast to Blois (crossing the Loire), then southwest to Bordeaux (several nights) – St. Jean de Luiz – Hendaye (Spanish border) – San Sebastian (overnight) – Bilbao – Lisbon.

Lisbon then was full of diplomatic intrigue, competing intelligence activities, and persons and families displaced by the war, attempting to reestablish their lives. No accommodations were available in crowded Lisbon, but the authorities arranged for a hotel about 50 miles to the north, in the town of Caldas da Rainha. The town contained military barracks and a small garrison and their hotel overlooked the market square. While Max and OK commuted to Lisbon to arrange their affairs, Anne and Herb, not attending school, had time for relaxing, including visiting the beach at the coastal town of Figueira da Foz, about five miles to the west.

Fortunately for Max and OK, the trip they had planned to New York facilitated booking a flight on the Pan American Clipper from Lisbon instead, while their visas had already been arranged. Moreover, In New York they had business and financial contacts. Suddenly the fates turned against the family. Young Herb tragically contracted polio, often a death sentence in that pre-Salk vaccine era. Max somehow found a Doctor Diago Furtado in Lisbon, who had interned at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore and took Herb into his care. Herb recollects riding in the ambulance south to a Lisbon hospital, his body unable to move, accompanied by his mother, having to traverse seasonal wildfires raging on both sides of the road for about 15 miles.

Max had gone ahead to Lisbon with Anne, for he not only had to make preparations for admitting Herb, but also had arranged for Anne to live temporarily with a friendly family, in their spacious Lisbon apartment, where a daughter of the house would keep her company while the parents saw to Herb’s care. When Max flew to New York it was with a heavy burden, but he was able to arrange entry visas for his family. At length their prayers were answered. Herb slowly recovered under the doctor’s skilled care, until well enough to travel. It was almost a miracle.

Meanwhile, 16 year old Anne, in her father’s absence, had assumed some of his responsibilities, especially concerning their travel to the US. Later, as a grown woman, she still remained bitter about seemingly needless delays and bureaucratic obstacles imposed by the American consul in Lisbon, whom she considered an evil person. Eventually the three of them boarded ship, the “Siboney,” for the dangerous trip west to join Max. The voyage to America was to provide one more frightening moment when their ship, flying US colors, was stopped in mid-ocean by a German submarine. Fortunately a state of war did not yet exist with Germany (Germany would declare war on the US four days after Pearl Harbor) so, after checking its papers, the ship was permitted to proceed, and they gratefully disembarked in New York harbor on December 10, 1940.