Szajko

Visa Recipients

- SZAJKO, Estera née CZERNIEWICZ P A

Age 30 - SZAJKO, Mireille P A T

Age 1 - SZAJKO, Raymonde P

Age 5 - SZAJKO, Szlama P A

Age 31

About the Family

The SZAJKO family received Portuguese visas in Toulouse signed by honorary vice-consul Emile Gissot on July 12, 1940 under the authority of Aristides de Sousa Mendes.

They crossed into Portugal and sailed to New York on the vessel Nea Hellas in August of 1940.

- Photos

- Artifacts

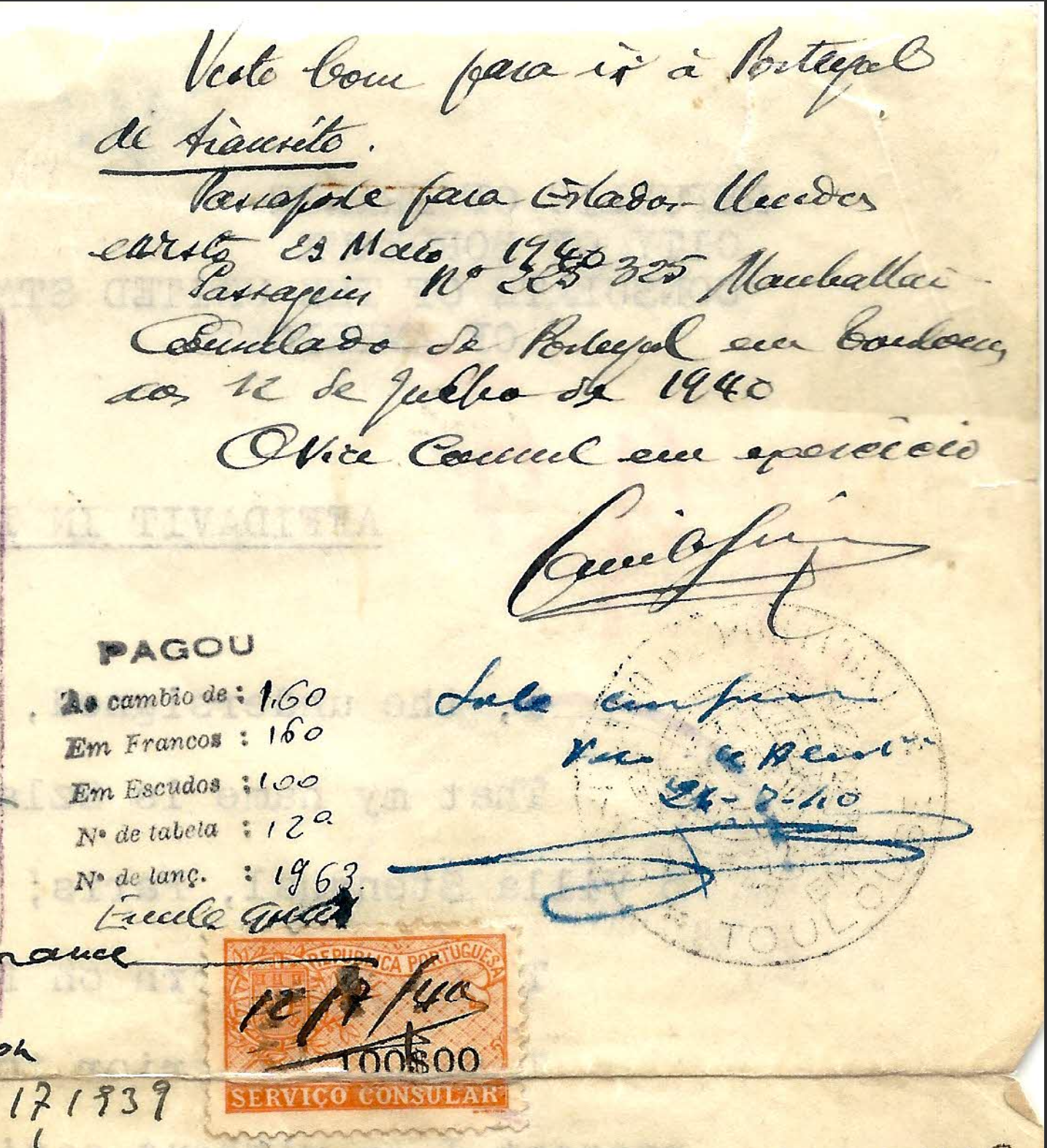

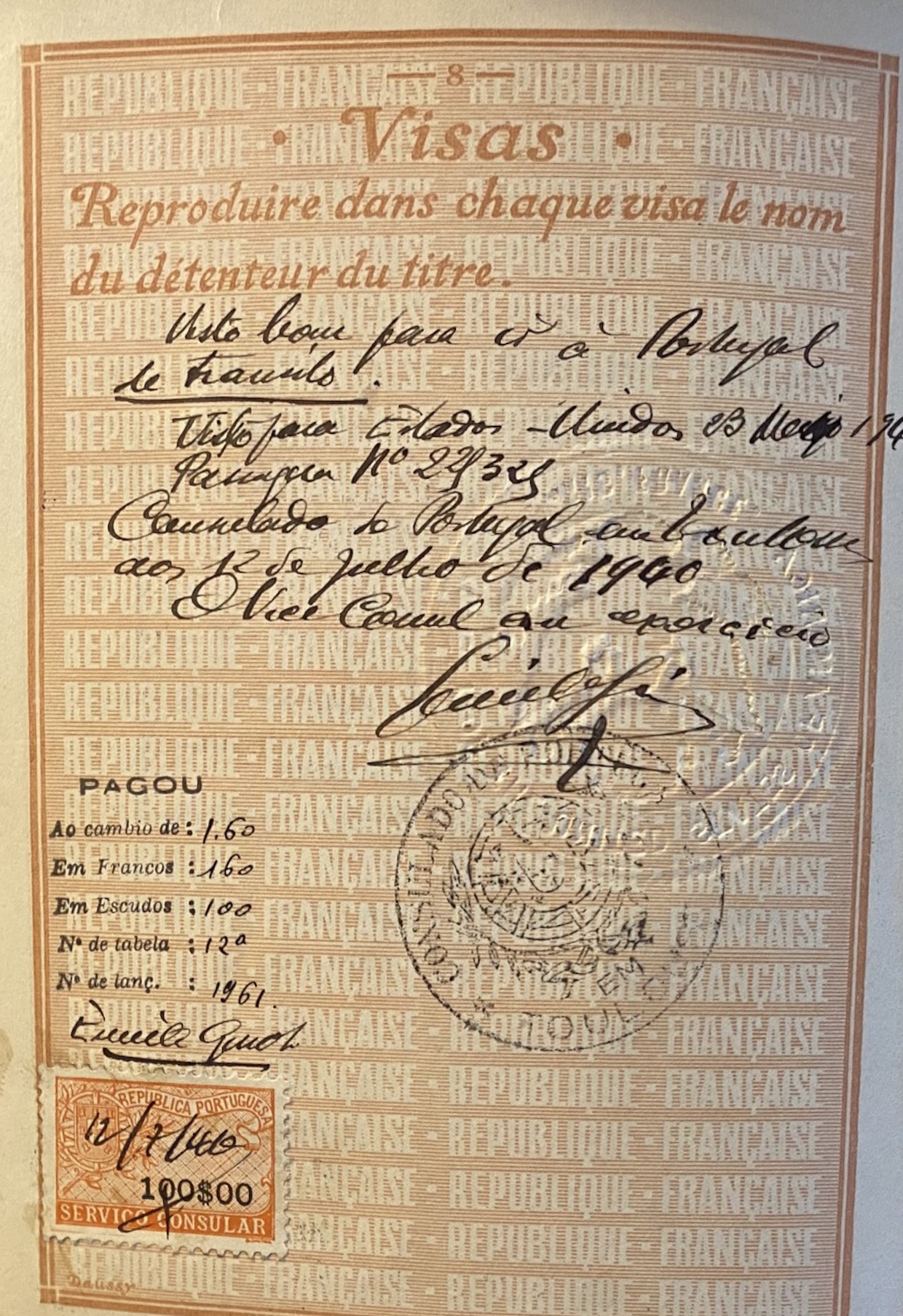

Portuguese visa issued to Estera SZAJKO in Toulouse on July 12, 1940 signed by Emile GISSOT under the authority of Aristides de Sousa Mendes

- Testimonial

Testimonial of Mireille Taub née Szajko

Last Train from Paris: Escape and Refuge, 1940

I was born in Paris, on October 7, 1938. The world political situation was rapidly worsening due to the rise of Nazism in Germany. My maternal grandmother, wise to the ways of deteriorating social conditions because of her Polish background, urged my parents to arrange to leave France should conditions worsen.

Both my father and mother were born in Poland.... One of the major impediments to obtaining the appropriate visas was the fact that because my father, having left Poland before the age of conscription, had never served in the Polish National Army, he therefore was not recognized by the post war government as a legal citizen of Poland.... Nansen passports, named after the Norwegian diplomat who sponsored these papers, were issued by the League of Nations to people that were unable to prove a national identity. Approximately 2000 in total, they were mainly issued to White Russians, who, after the Russian Revolution needed to immigrate to safe places. I suppose that perhaps my father was able to be issued a Nansen Passport because the village in which my father was born was on that fluctuating border between Russia and Poland.

Although my sister and I were both born in France, my parents had to petition the French Government for citizenship status, which was granted, but not without filing numerous papers and fees. The years between 1934, my sister’s birth and 1938, when I was born were filled with increasingly serious international, political and economic crises. War became inevitable in spite of Chamberlain’s optimism. Papers, affidavits, visas were submitted, returned, and recognized. Passport applications were filed, received, and placed within accessible safe keeping....

With the advent of hostilities, my father immediately petitioned the American Consulate for evacuation and began to prepare an escape route via Bordeaux to Spain. In fact, he traveled to Bordeaux hoping to be able to send for us or send us along during the beginning stages of the phony war. Paris was under constant bombardment alert and although not many bombs had actually fallen, the citizenry, terrified, sought nightly refuge in makeshift bomb shelters built under apartment building cellars and in the Metro. Gas masks, resurrected from the First World War, and some, reissued, were constant companions. Ration tickets for supplies such as food, coal, and clothing were issued to prevent stockpiling, looting and black marketeering....

We stayed in Perpignan very briefly and found some means of crossing the mountains into Spain. I am not sure how this was done, but I am sure it was extremely dangerous and my parents were sure that, despite their exit visas, they could be sent back into Occupied France and into prison camps and worse.

Once in Spain, we traveled by train to Barcelona, allowed only to travel through Spain, but not stay in Spain. From Barcelona, we traveled to Lisbon and embarked on a Greek tramp steamer. We spent three weeks crossing the North Atlantic, trying to avoid U-boats, looking to torpedo ships heading towards America. We arrived in America on August 11, 1940. My father’s journal records a terrible voyage. Boat tickets show hammock beds, probably a very cramped stateroom and less than adequate fresh food.

Six weeks of travel across war zones in France, Atlantic storms, U-boats, grossly inadequate and horrible food had finally taken their toll on me. Upon our arrival at Ellis Island, immigration doctors told my parents that I was too ill to be taken off the Island. I had a fever, broken out in hives and was a very unhappy toddler. My mother successfully convinced them that there was nothing more serious than the accumulated stress of our experience.

We were extraordinarily lucky to be able to escape France. Other family members were not.