There is a Mirror In My Heart | An Exhibition

About the project

There is a Mirror in My Heart is a personal artistic response by artist Sebastian Mendes to the action of his grandfather, Aristides de Sousa Mendes. The project includes three components, as follows:

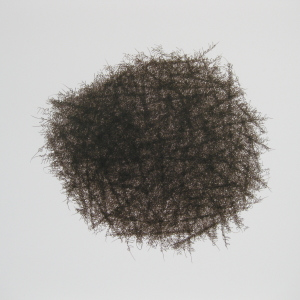

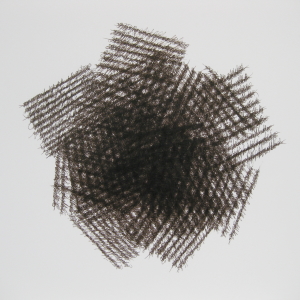

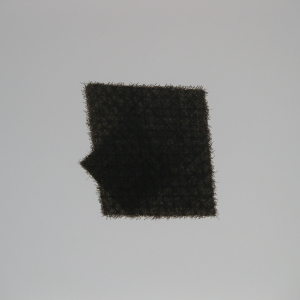

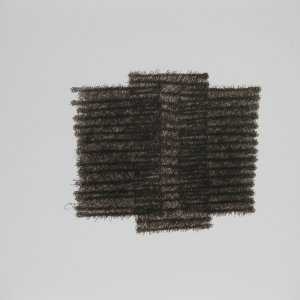

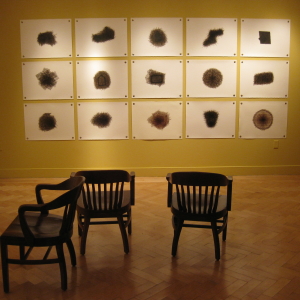

1) Palimpsest Drawings, an ensemble of thirty 24” x 30” ink drawings of heavily superimposed writing, recalling signatures, written over each other to create a palimpsest, representing the thousands of desperate refugees who were saved by Sousa Mendes’ actions. Each drawing is the product of a simple reverent gesture of remembrance, writing a number, refugee’s surname and the signature of Aristides de Sousa Mendes, as it would have customarily been written upon transit visas.

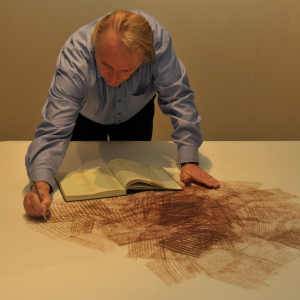

2) A continuous performance action work in the gallery, inscribing the surnames of the refugees who received transit visas from Sousa Mendes. These performance actions would take place over the course of the exhibition. The drawing’s is a seven-foot by seven-foot sheet of Japanese Hiromi Daitoku paper. The drawing has been worked on a large sculptural table, designed to evoke the conjoined appearance and function of a large consular desk with a functional drawing table. Each of the surnames included in the large panel will also be inscribed into a numbered ledger, like the original consular ledger used by Sousa Mendes. This performance action work has an important social component of directly engaging with visitors to the exhibition who will be able to discuss the work with the artist and join him in pondering the meaning of Aristides de Sousa Mendes’ historic actions.

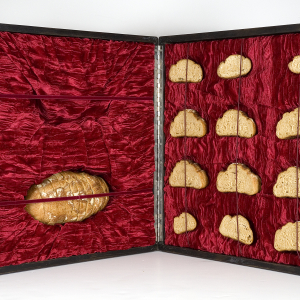

3) Bread Reliquary Suitcases. Bread is a multivalent symbol. In this project the inclusion of loaves of bread bearing Anglicized Jewish names made of bread dough will symbolize both the refugees themselves and their adaptation to new cultures in the lands where they found safety. Such loaves and slices of bread will be set in a variety of suitcases.

Further comments by the artist on the performance action: The drawing was the result of a simple process; writing onto the paper a number, followed by a refugee’s name, followed by name of another man Aristides de Sousa Mendes, whose lives had been briefly but deeply connected. This process of numbering and naming would eventually be repeated thirty thousand times randomly across the surface of the drawing, while engaging with visitors to tell the story of my historical and artistic motives for drawing in this particular way.

As a still in-progress work, the drawing has by now formed a dark and impenetrable mass of superimposed ink lines at its center with a calligraphic arabesque around the edges. Although illegible, it was still recognizable as handwriting.

These drawings have been my personal creative response, as a contemporary artist to the legacy of my grandfather.

From the earliest memories of my childhood and the Holocaust, my grandfather’s actions have been deeply connected to the oral history of my family, and his story has been a formidable presence in my daily life. Increasingly, since that time, I have become more deeply impressed by the magnitude and magnanimity of what he had done for so many refugees of the Holocaust. His total moral, psychological and physical commitment to achieving what he knew he must, was huge and beyond my capacity as a boy to even begin to comprehend or respond to. The enormity of this incredibly demanding physical act in and of itself seemed a subtle yet complex symbol of the entire event.

Ever since my days as an art student, I had wanted to make art that would be a tribute to his legacy and at the same time remain true to my interests and practice as a contemporary artist. I mulled this question over for a long time. Eventually, I realized that a way into doing this could be found in drawings that I had been making for several years. Through repeated superimposed writing/drawing of texts that had been important to me, their specific content was no longer legible to others but had become a personal private act of contemplation.

The first part of this drawing at Jewish Museum of Australia had begun earlier, at the International Drawing Research Institute’s conference Marking Time, at College of Fine Art, in Sydney. I had gone to COFA with my original intention being not to imitate or emulate his actions under extreme duress of working tirelessly around the clock for several days and nights as he signed lifesaving visas, but to humbly, and reverently remember him and those he had saved through the act of drawing the names of as many refugees as I could, during a continuous and concentrated period of five days. An important component of the process was to engage with any observers who may care to discuss the history and contemporary art ideas surrounding the project.

Single Very Large Drawing:

The act of producing one very large drawing is a physically intense, goal-oriented action of significant and sustained duration. I would like to continuously occupy and work in the gallery for approximately five to seven days and to quietly work as long as I am physically able, stopping for the briefest periods and only when absolutely necessary. Each day, the exhibition and viewing of the installation will progressively change. I will work in the space, in response to the then current physical and social dynamics of the installation; depending on the way in which visitors to exhibition will interact with me or respond to each other.

I see the time during which this one large drawing is worked on in the gallery as an intensely concentrated yet protracted period to recall and reflect upon the experience of my grandfather’s actions of sixty-seven years ago, and that it is a public setting that offers the opportunity to share this story and the discourse surrounding it with others. Similarly, the series of smaller drawings completed in my studio, before the exhibition allows me to privately immerse myself in the content and meaning of what my grandfather’s legacy may mean to me. Both experiences may yield insights into possibilities for new work.

I would design the aforementioned drawing table so that it simultaneously referred to itself also as a great desk from a consular office, with distorted perspective, perhaps similar in appearance to the seemingly odd perspective in some northern Renaissance and illuminated manuscript images.

While in the gallery, this drawing-action process would be amenable to spontaneously engaging in some discourse by responding to students’ and visitors’ queries or remarks. I would invite anyone who knew the names of victims or survivors of the Holocaust to participate by adding those surnames to the ledger book. We could also have a didactic or interactive project website beforehand. Individuals who knew names could enter them into a web-list, which could in turn be melded into the drawing action. Note: The ledger book with names of refugees could be prepared beforehand. We could form a website for the project, where individuals could submit the known names of survivors and victims as well as those who narrowly escaped persecution and murder.

This Project was realized at Yeshiva University Museum, New York, and Centre des Archives Gironde, Bordeaux France. Portions of the project were also presented at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, The Jewish Museum of Australia, Melbourne and the Consulat du Portugal, Paris.